Module 5 part b

Honouring the artisan

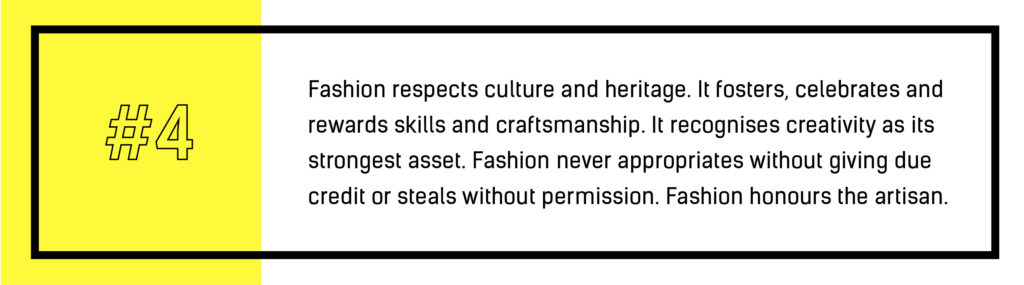

We finish this module – and this course – by looking closely at Fashion Revolution’s manifesto point #4. It pictures a time when the craft knowledges, skills and heritage that today’s fashion system is built upon is properly recognised and rewarded.

QUESTION: How close do you think we are to this now? What do you think? Write down your thoughts.

In this lesson, we look at the world of fashion, its ideas, traditions and heritage before the fast fashion model began to take hold in the 1980s. So we look at the designs, skills, creativity and craftsmanship that have been passed from generation to generation to make culturally distinctive clothing designs and materials around the world. We look at the ways in which these ‘traditional’ ideas and practices survive (or not) into the present day, how they are routinely appropriated and sold by Western brands without recognition or payment, and how the artisans whose traditions have been stolen are fighting back. By doing this, we change the emphasis of Fashion Revolution’s ‘who made my clothes?” question. Here, the answers become more historical and focus on fashion heritage, the ownership of designs, and the artisan as another hidden garment worker to honour and treat with respect.

We start by looking at modern fashion designers who draw on their cultural heritage to bring ‘traditional’ designs and practices into today’s fashion industry. We then look at some notorious examples of ‘traditional’ designs being stolen by Western brands through a process known as ‘cultural appropriation’ and ask if and how consumers can be guilty of this too. We then take a look at three communities who are fighting back against cultural appropriation by the fashion industry by trying to get recognition that their designs have been stolen and that the wealth generated from them should be shared with them to enrich their communities too. We then finish the module by asking you to reflect on where this course has taken you, what you might want to do next.

i. Fashion, culture and heritage

This course has focused a lot on tracing our clothes through their supply chains, finding out more about the people whose lives are connected by producing, processing, assembling and wearing their materials. But there is another type of tracing that we could do: the tracing of the ideas and inspirations for the design of these clothes. This tracing stretches back to a time before most people’s clothes were manufactured in huge factories thousands of kilometres away from the people who would wear them. When their designs, materials, making and wearing were more tied to particular places. When clothing designs and skills, worldwide, were much more diverse. These designs and skills are said to be dying out, but many survive, and new generations are being encouraged to develop them as an expression of their heritage and as a way to make a living.

TASK: Watch this 6 minute two video playlist in which designers Fern Chua and Gabriela Martínez Ortiz explain what Malaysian Batik and Mexican embroidery mean to them.

QUESTIONS: Why did Fern and Gabriela turn to more ‘traditional’ approaches to textile and clothing design in the countries where they live? How different does their work seem to be to the fast fashion model we have learned about in this course? Are they producing clothes just like their ancestors, or are they doing something else too?

EXTRA STUDY: read about other examples of traditional forms of textile design and making – like the Rebozo shawl from Mexico (p.10-11), the Mola blouse from Panamá (p.18-20), Chakan embroidery from Tajikistan (p.28), the Ojiya-chijimi and Echigo-jofu techniques of fabric making from Japan (p.29) and Harris Tweed fabric from the UK (p.58-9) – in Fashion Revolution’s 2020 Fanzine Fashion Craft Revolution here.

ii. The concept of ‘cultural appropriation’

Manifesto point #4 is a response to a fashion industry that hasn’t always respected culture and heritage, has routinely appropriated without giving due credit, and has stolen without permission. We have covered aspects of this problem in previous modules: asking what our clothes can say about us (Module 1a), learning about the lives of people working in fashion’s supply chains (Module 1b), understanding the cultural diversity and intersectional solidarity in fashion activism (Module 3a) and recognising the unequal voices and power relations of the people wanting change to take place (Module 4a). Since the 2000s, many many brands have been called out for ‘cultural appropriation’. But what does this concept mean?

TASK 1: Flick through the ‘cultural appropriation’ slideshow below to see which brands have been accused of ‘cultural appropriation’.

QUESTIONS: Which brands have been called out? What clothes were their models inappropriately given to wear? What seems to be the problem?

XXX

TASK 2: so, what exactly is ‘cultural appropriation’? Here we turn to fashion academics and journalists to explain this important concept. There are 6 quotations to read, with the following questions in mind.

QUESTIONS: How would you define ‘cultural appropriation’? Why does this happen? Who appears to benefit from stealing whose knowledge and heritage? What do the communities whose designs have been stolen get in return? Is this ‘stealing’ or something else? What experience, if any, do you have of this concept?

Cultural appropriation “implies that a more powerful culture is using another less powerful culture. … [It] only happens when there are power inequalities between different cultures [and we] are still living in a world where white people and institutions are much more powerful than black or brown people and their institutions” (Serkan Delice in BBC 2018).

“Designers have gone around the world cherry-picking from other country’s material cultures, and then using it as if that’s exactly what other cultures are there for. And it feels quite disrespectful to these other cultures. Because there’s no discussion. There’s no benefit. There’s no acknowledgment. … if someone in a position of power is using the materiality of another culture for profit and gain without benefiting that culture or community in any way, then it is appropriation and heinous in the extreme” (Teleica Kirkland in Women’s Wear Daily 2020).

An example: “Gucci … faced backlash for cultural appropriation following its fall 2018 runway show, which featured white models wearing turbans. Further discontent ensued when the brand had the turban on sale at Nordstrom for $790. The Sikh Coalition, named for the religious group that dons the cloth head wraps as part of a religious observance and which advocates for religious rights, had this to say on social media: “The turban is not just an accessory to monetize; it’s a religious article of faith that millions of Sikhs view as sacred. Many find this cultural appropriation inappropriate, since those wearing the turban just for fashion will not appreciate its deep religious significance.” What the move also failed to address, critics said, was the harassment or mistreatment that people who wear turbans for religious reasons often face while wearing them. As a fashion piece, Gucci’s turban would profit in the face of that” (Teleica Kirkland in Women’s Wear Daily 2020).

Cultural appropriation happens because, “Traditionally, designers were taught at fashion schools to pick and mix from the world around them, be that from an art exhibition, film, the natural world, or the culture and heritage of global communities … We’re all drawn to an exquisite piece of embroidery, a colourful textile or even a style of dressing that might have originated from another heritage. [But] this magpie mentality, where all of culture and history is up for grabs as ‘inspiration’, has accelerated since the proliferation of social media. … Where once a fashion student might research the history and traditions of a particular item of clothing with care and respect, we now have a world where images are lifted from image libraries without a care for their cultural significance. It’s easier than ever to steal a motif or a craft technique and transfer it onto a piece of clothing that is either mass produced or appears on a runway without credit or compensation to their original communities” (Tamsin Blanchard in BBC 2022).

But it’s possible to work across cultures in more positive ways. For example, “A lot of European designers like to borrow aspects of African cultures, whether it’s beaded decoration or a certain kind of printed fabric. … If they made some kind of an alliance with people and acquired embroidery or fabrics from actual African producers and promoted the collaboration, they would undercut the idea that they were just exploiting and appropriating. … Who is having conversations with people? … This is what needs to change. Speak to the people, pay respect to the people in these places, talk to teachers, the designers, the artists, talk to the people who are actually in these places and say, ‘Look, I’m finding it really interesting. And I’m thinking about making a collection about this, what do you think?’ Acknowledge what’s happening for them in their environments, don’t just grab interesting ephemera and run!” (Teleica Kirkland in Women’s Wear Daily 2020).

So, Teleica Kirkland asks, “Is the ability to use other cultures’ materiality the only place creativity comes from? I find this question a bit irritating, to be honest, as it suggests that the only purpose for the existence of non-Western cultures is to provide an exciting cultural dressing up box for the West. … This is such an incredibly old-fashioned and narrow-minded way of thinking. Why aren’t designers exploring more of their own heritage and using their own backgrounds as foundations for their work? The question must always be asked, what is so fascinating about someone else’s culture? This requires introspection, knowing yourself very well, and moving forward with positive intention” (in Women’s Wear Daily 2020).

EXTRA STUDY: for more details about how designers and brands could respectfully and fairly work with the intellectual property of artisans, communities and cultures around the world, read this article from the World Intellectual Property Organisation.

iii. The experience of ‘cultural appropriation’

All of the examples mentioned above are from high fashion catwalk shows and collections, and see the problem of ‘cultural appropriation’ as something to be addressed only by designers and brands. But what about fashion’s consumers? In a world whose populations have historically mixed through centuries of migration, and in which mass tourism and the internet have fostered opportunities for all kinds of cultural exchange as well as appropriation, how easy is it to say that this is ‘my’ culture and this is ‘your’ culture, and that one is ‘appropriating’ the other? This is a question that was put in the film below to people attending a music festival – one of many places where people often ‘dress up’ in the ways that are criticised above.

TASK 1: Watch this 9 minute BBC video in which people attending a music festival in the UK are asked about the ways in which they ‘dress up’ in ‘other’ cultures’ clothing. Listen carefully to their arguments and answer the questions below.

QUESTIONS: How do the people wearing the clothes of ‘other’ cultures explain why they do so? Does it seem that anyone has called them out for doing this? What do they say they might do if someone did? Why do you think that doesn’t seem to have happened? According to one of the people interviewed, is it only white people who have the power to problematically appropriate the clothing of ‘other’ cultures? Why not? What’s your experience of fashion’s ‘cultural appropriation’? How do you feel about this?

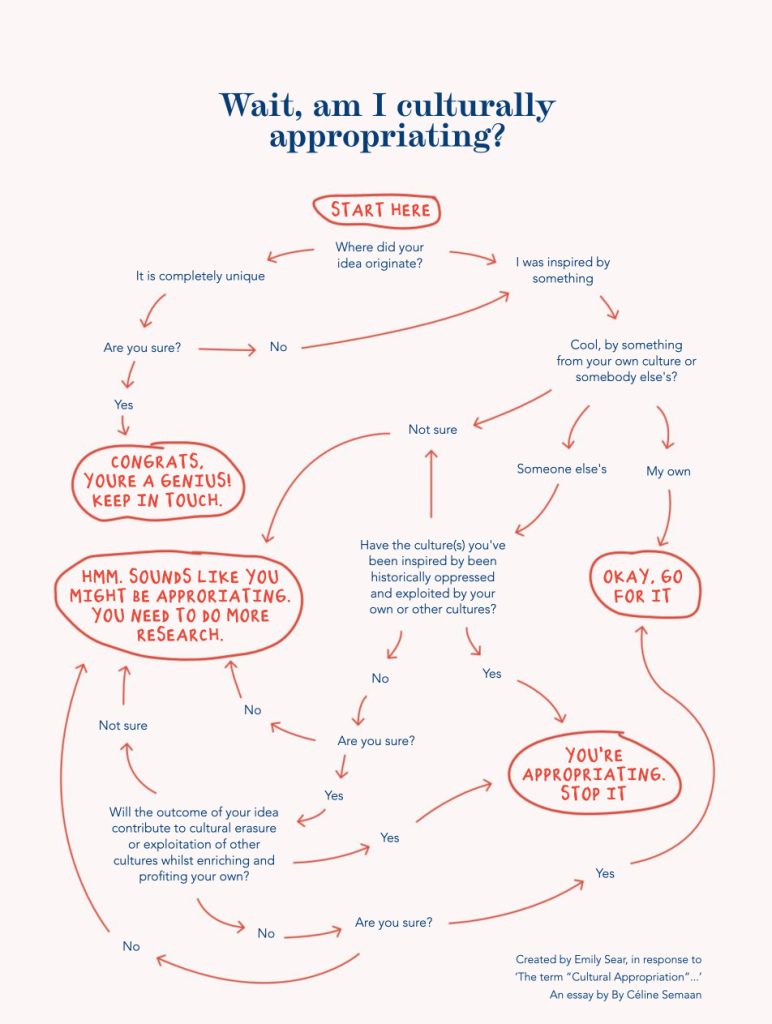

TASK 2: Imagine that you are a fashion designer rushing to create a new design for a hot summer clothing line. OR imagine that you are going to a music festival and are talking with your friends about what you’re planning to wear. Either way, you’re looking for ideas and inspiration but you’re concerned that someone might call you out for ‘cultural appropriation’? You quickly pick an item of clothing from a magazine, a website or your wardrobe, without thinking too much about it (do this please!). You have been given Fashion Revolution’s ‘cultural appropriation’ flow diagram to see if there might be a problem. You start where it says ‘start here’ and see where the questions and answers take you.

QUESTIONS: Where does the item of clothing that you have chosen take you? What does the diagram suggest that you do next? What happens when you try other items of clothing? [Try one that you think isn’t, and one that you are 100% sure is, a ‘cultural appropriation’.] What do you think about the concept of ‘cultural appropriation’ now?

iv. Community responses

It is quite easy for the artisans, communities and cultures whose designs have been appropriated to find out that this has happened. But what can they do in response? What kind of pressure can they put on brands both to acknowledge that these designs are theirs, and to be compensated for this ownership financially?

TASK: Watch this 9 minute 3 video playlist in which artisans in Mexico, Laos and Bulgaria respond to the cultural appropriation of their designs by Mango, Max Mara and Dior. As you do this, take some notes in answer to the following questions.

QUESTIONS: What can happen when communities complain to brands about their cultural appropriation? Who owns the designs that have been stolen? Why can this be a problem? What do community members think of the versions of their designs that are made by brands? If brands paid communities for the designs they have stolen, what could those communities do with the money? What other options do communities have to gain recognition and income from their designs?

EXTRA STUDY: Fashion Revolution’s (2020) fanzine Fashion Craft Revolution contains the detailed thinking behind Manifesto Point #4. Read it here if you want to learn more.

iv. Reflection

Congratulations for completing the course! We hope you have enjoyed learning what’s behind all ten of Fashion Revolution’s Manifesto Points. By looking at these last two Points here, we have imagined a fashion system that works very differently to the fast fashion model that we are so used to. But it’s not quite the same as the circular fashion system. No alternative fashion system is without its problems – which we have not shied away from – and both the artisanal and circular systems have the potential to provide the kind of practical, affordable, sustainable and just fashion system that Fashion Revolution is working towards. Like every one of its Manifesto Points, we know that these alternatives are possible because they are already coming into being. But none of this change will happen on its own. None of this will happen without people understanding and using their powers of persuasion, solidarity and activism of many kinds. None of us can do everything, but all of us can do something. So there are a couple of tasks to end on.

TASK: Now you are an expert on Fashion Revolution’s Manifesto and the kind of fashion system it wants to bring into being, please consider signing it. Click this link, check what it asks you to do and make your decision.

QUESTIONS: Why did you (not) sign the Manifesto? How do you think your signature can help to create the fashion system the Manifesto imagines? What does the Manifesto page say? For you, what is the main purpose of this Manifesto?

This course has been designed around Fashion Revolution’s mantra: ‘Be Curious, Find Out, Do Something’. It has asked you to do all three, in every module! Now you have reached its end, we’d like you to reflect on where this course has taken you and what might be next.

- What caught your curiosity the most?

- What have you found out most about?

- Now you know, what can you do?

Everyone’s answers will be different. And there are no right or wrong answers. As usual, please express your answers in any way you like: writing, sketching, photoshopping, whatever works for you!

Thanks for taking part.