Module 2 part a

Environmental impacts of fashion

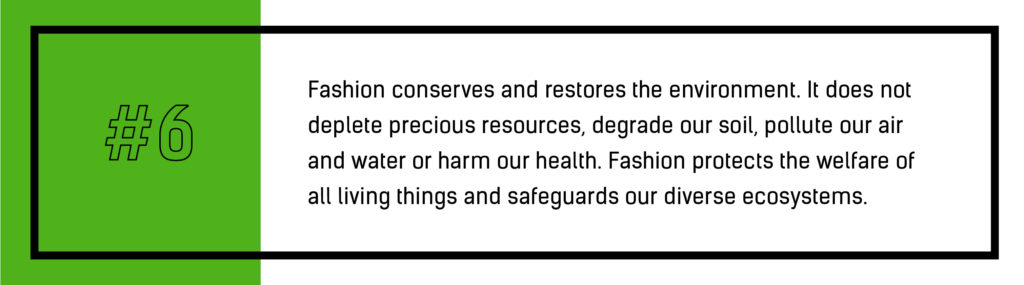

Let’s start this module by looking closely at Fashion Revolution’s manifesto point #6. It pictures a time when the fashion industry does not exploit but works in harmony with the environment.

QUESTION: How close do you think we are to this now? What do you think? Write down your thoughts.

When fashion brands decide that their latest lines need to be made from particular materials, they are not only deciding what’s comfortable or stylish for us to wear, but also what’s comfortable for people working in and around the sites where those materials will come from and end up.

In the last module, we looked carefully at the statements that our clothes make in the world and the people who make them. In this module, we take a closer look in:

- part a) at the materials that our clothes are made from and what is in them – their fibres, their fabric, their colours, their finishes and the ecological damage that these can leave behind – and in

- part b) at the alternative clothing choices and economic models that could help to clean them up.

We start this module with a simple question:

i. Can fast fashion be eco friendly?

This is the question that was answered in a 12 minute episode of Deutsche Welle’s Planet A series. It finds out what’s in our clothes, shows why it matters to ask about this, and talks to people who care about how fashion’s supply chains can affect our environments.

TASK: We would like you to watch this episode and to pause it every now and again to take some notes in answer to the following questions.

QUESTIONS: Where in fashion’s supply chains are ecological problems caused? What kinds of processes cause these problems? Who experiences these problems? What kinds of ecological problems are associated with different materials, like polyester and cotton? What efforts are being made to reduce these problems? What more is there to do? Can fast fashion, as the video’s title asks, be eco-friendly?

ii. Focus – pesticide use in cotton farming

There are lots of issues that we could focus on in this video, but we’re going to choose two. Pesticide use is the first. Here, we’re going to ask you to look in more detail at the properties of cotton clothing that make it so popular, the use of chemicals called pesticides in the farming of cotton, the effects that pesticides can have on people and the environment, and the difference that growing cotton organically can make.

READING TASK: read the following extracts from academic, news, NGO and corporate sources to learn more about pesticides in cotton. Then answer the questions at the end.

Cotton fabric is versatile to work with and comfortable to wear. According to textile scholars V.K. Dhange, S.M. Landage, and G.M. Moog this is because:

“Cotton is a white, feathery fibre, and individuals consider cotton to be a pure, natural cellulosic fibre. Cotton is a fantastically multipurpose and worldwide significant fibre that is employed for a wide range of fabrics. As a result, it is one of the most extensively traded commodities on the market. Cotton fibres have a high market value due to their versatility, absorbency, softness, breathability, and durability. Cotton is not only the most communal and successful fabric, but it also has the highest marketable price of any cloth.”

But cotton is a difficult crop to grow and to harvest. It’s vulnerable to all kinds of attacks. So, as sustainability writer Brooke Roberts-Islam explains:

“Cotton farmers use a variety of pesticides that target insects (insecticides), weeds (herbicides), and fungal infections (fungicides). They also use growth regulators, and defoliants to aid mechanical harvesting. The majority of cotton seeds come pretreated with insecticides and fungicides, and additional pesticides are used on soil (to control weeds, fungus, and insect pests), and as an application on the cotton crop.”

According to the NGO Pesticide Action Network, “cotton supports around 100 million rural families” in 80 countries, and 80% of the world’s cotton is grown in just 6 countries: Australia, Brazil, China, India, Pakistan and the USA (PAN 2018, link). Recent studies have suggested that pesticide use is declining worldwide, and that pesticides can be more or less safely applied in different forms of cotton farming. But the 13 most widely applied pesticides can have harmful effects, for example:

“Acephate … [is ] used normally as a foliar spray to control chewing and sucking insects [like] Aphids; Leaf miners; Lepidopterous larvae; Sawflies, Thrips. … [but] can overstimulate the [human] nervous system causing nausea, dizziness, confusion, and at very high exposures (e.g. Accidents or major spills) respiratory paralysis and death … [and] is highly toxic to bees and other beneficial insects. …

Acetamiprid … [is used as a] ground and aerial application against Aphids; Thrips, Mirids, Spider mites; Whiteflies. … [but] can cause [human] eye irritation, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, dizziness, headache, … mild sedation, … adversely affect the development of neurons and brain structures associated with learning and memory functions … [and] is highly toxic to birds and earthworms and moderately toxic to aquatic organisms.

Glyphosate … is sprayed on … genetically modified … crops [including] … cotton … to target annual and perennial weeds [and] grasses. … [but] long term exposure can lead to kidney and liver damage and it has been classified … as probably carcinogenic to humans. … [and] can affect soil micro-organisms, earthworms, birds, bees and plants.”

But there is an alternative form of cotton farming without these harmful pesticides. This farming produces organic cotton which, according to textile scholars V.K. Dhange, S.M. Landage, and G.M. Moog, is: “cultivated with environmentally friendly processes and ingredients. Organic farming practices reload and preserve soil fertility, restrict the application of potentially hazardous substances and insistent herbicides and nourishments, and promote biological diversity. Certification by third-party bodies ensures that organic farmers utilise approaches and resources approved for organic production. Organic farming is founded on the notion of working with nature rather than against it. Organic farmers raise crops using biologically-based methods rather than chemically-based methods.”

According to Textile Exchange, the global production of certified organic cotton has been increasing for a number of years – from 107,790 tonnes in 2015-16 to 342,265 tonnes in 2020-21 – with the top 3 exporting countries being India, Turkey and China.

But, in their 2021 report, they said that “even with this growth, organic cotton still only represents roughly one percept of the global cotton harvest … That’s not enough.”

QUESTIONS: Why do some argue that cotton needs pesticides to grow well? What problems can these chemicals cause for people, plants and animals in and around cotton farms? Can cotton be grown without pesticides, and what else has to happen for this to be possible? Is the growth in organic cotton production enough to make fashion’s supply chains more sustainable? What do you think you can do to help accelerate this growth?

EXTRA STUDY: Please click any of the links above to find out more.

iii. Focus – fabric-processing & river pollution

For our second focus, we move to the textile mills where raw fabrics like cotton – usually a yellowish-white colour – are processed before being shipped to the garment factories where they are cut and sewn to make clothes. Here, for instance, we’re asking you to think about the colours you like to wear, and the impacts that they can have on the environment in the places where they were added to the fabric.

There are three parts to this section. First, we take a quick look at the processes that raw fabrics have to go through before they are ready to be made into clothes. Then we will watch a short video about one place where the chemical waste from some of these processes ends up. We will then finish by looking at some more environmentally friendly chemicals that can be used to process, and add colour, to our clothes.

Fabric processing

QUESTIONS: How is raw fabric processed in textile mills? What properties does this processing give to the fabric? Which processes use chemicals?

There are a number of processes that take place in textile mills to turn raw fabric into fabric that is ready to be made into clothes. For organic fabric like cotton or wool, these can include, for example:

- singeing (burning off yarns and fuzz that stick out to produce an even surface by)

- desizing (dipping in acids or enzymes to remove starch)

- scouring (boiling with chemicals to remove fat, oil or wax)

- bleaching (using chemicals to remove natural colour)

- mercerising (using chemicals to swell fibres to change texture, strength and the ability to take dyes)

- dyeing and/or printing (using chemicals to add colours / patterns that will fix them permanently to the fabric)

- finishing (using machines or chemicals to make surfaces fluffy or flat, and to make fabric crease-proof or fire-resistant)

EXTRA STUDY: if you would like to know more about fabric processing and the chemicals that are used, please read the International Chemical Secretariat’ guide here.

Water pollution

QUESTIONS: What happens to all of these chemicals afterwards? Where does this chemical waste go? What can it do there? What and who can it harm? Whose responsibility is this?

Here, we return to Deutsche Welle’s Planet A series to watch a 12 minute episode which shows what happens to the garment industry’s chemical waste in the city of Tirpur in India.

Natural dyes – a solution?

QUESTIONS: Can other chemicals that are less harmful to the environment be used to process the fabric in our clothes?

We finish this section with a look at an alternative type of chemical that can be used in fabric processing: ‘natural’ dyes. The dyes used in the fashion industry tend to be synthetic chemicals derived from oil, but there are more ‘natural’ sources of colour in our clothes. According to textile engineer Arun Kanti Guha, fabric dyes can be made from many natural sources, including onion skins, black carrots, barberry bark, orange and lemon peels, marigold flowers, turmeric and tea.

However, as textile designer Beth Ranson argues, buying garments whose colour comes from ‘natural’ dyes may not make a big difference to the garment industry’s chemical waste problem because: “Though natural dyes have connotations of wholesome, toxin free textiles, this is not necessarily the case. … Though the dye materials themselves are not pollutants to water, the chemicals employed to fix the colour to the fibres are.”

So one important question to ask here is how many of the toxic synthetic chemicals that are now used to process fabric could be replaced by ‘natural’ non-toxic alternatives. Or we could look at this another way, and ask what brands and retailers could do to help textile factories safely process their toxic chemical waste water before releasing it into the environment.

EXTRA STUDY: if you would like to look at this issue in more depth, click the link to Beth Ranson’s article and see what she says.

iv. Reflection

When we start to ask ‘what’s in my clothes?’ the simple answer is ‘a lot’. In this first part of Module 2, we have only looked at chemicals (not, for example, greenhouse gas emissions), only looked at two places in the value chain, only looked at one kind of fabric and only looked at fast fashion supply chains.

TASK: to finish this part of the module, we’d like you to go back to the question ‘can fashion be eco-friendly?’ and to think about your answer by choosing an item of clothing that you love to wear and look for evidence of the chemicals that may have been used to make it. Your main source of information will be its labels. They help you to answer these questions:

QUESTIONS: what material(s) is this garment made from? Is it ‘natural’ (e.g. wool, cotton, linen), synthetic (e.g. polyester) or a blend? Does it say that it is ‘organic’?, crease-proof, flame-retardant or something else? Does it say something like ‘wash with similar colours’? Why? What could happen to its dyes in the washing machine? It will probably name the country where it was made. But that’s the country where its panels of fabric were cut and sewn together. Does it say where it was farmed, or made, or processed? Can the brand’s website tell you more? How eco-friendly does this garment seem to be? What information is easier and more difficult to find? Could these ideas and findings change the design of your statement piece, collection or brand?

You can express your findings in any way you like: writing, sketching, photoshopping, whatever works for you!