Module 3 part a

Inclusive, not exclusive, fashion

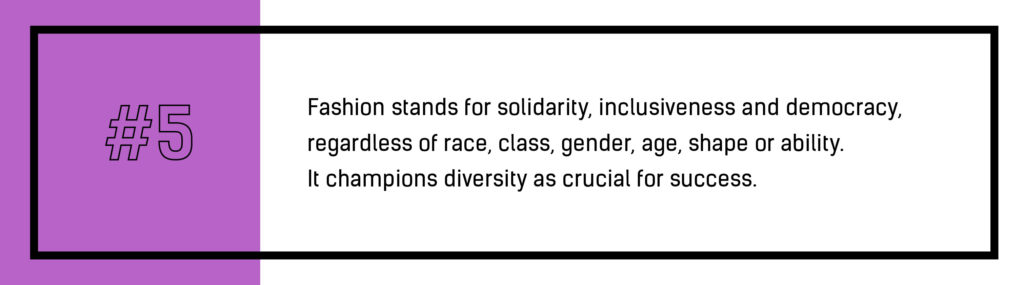

Let’s start this module by looking closely at Fashion Revolution’s manifesto point #5. It pictures a time when the fashion industry is organised for, and by, everyone.

QUESTION: How close do you think we are to this now? What do you think? Write down your thoughts.

Module 2a questions the ways in which fashion is often marketed as ‘exclusive’ when it could and should be the opposite, ‘inclusive’. We look at this issue, first, by looking at the photos of the people modelling the clothes we might buy and asking how much they look like us and our friends, and who is at work behind the scenes designing and photographing these fashion scenes for us to buy into. Second, we take a look further behind the scenes to ask if and how the inclusive politics that we, as fashion consumers, sometimes wear on our sleeves are at work through the supply chains that bring these clothes to us. Third, we look at the ways in which we can think about the similarities and differences between people working along fashion’s supply chains and, fourth, how this can help to shape solidarities that are essential for coordinated labour rights activism.

i. Making fashion less exclusive

When we hear about ‘exclusive’ fashion, it’s often upscale, designer brand clothing that’s made for wealthy people to enjoy. But Manifesto Point #5 is about its opposite: inclusive fashion. So, to start this module, we ask you to do three mini-tasks, each looking carefully at how – and on whose bodies – fashion is presented to us by brands and in magazines.

TASK 1: visit your favourite fashion retail and magazine websites. Take a look at the people modelling the clothes. How ‘diverse’ do they seem to be in terms of their skin colour, body shape and size, gender, age, and dis-ability? Do they look like you and your friends?

TASK 2: look through the photos of Jacquemus’ Spring 2021 ready-to wear collection show in Vogue and ask those questions again.

TASK 3: look at the photo Jaquemus posted after the show of the people working behind the scenes and ask those questions again.

QUESTIONS: looking through these photos, how exclusive or inclusive does fashion seem to be in terms of “race, class, gender, age, shape or ability”? Does this world of fashion fully include you and your friends?

FURTHER STUDY: the fashion industry isn’t as diverse as its consumers. Click these links to learn more about why this is the case, and how this might change, for people of colour, plus-size people and disabled people.

ii. Who made your feminist t-shirt?

If we want to create a fashion industry that stands for solidarity “regardless of race, class, gender, age, shape or ability”, what could this solidarity look like? People act in solidarity when they work with other people to challenge unequal power relations that they face as a group. If we take feminist solidarity as an example, this is where women work together to resist sexism, misogyny and gender-based exploitation, violence and inequality, and to claim full and equal rights for women as members of society. In an industry whose consumers and producers, overwhelmingly, are women, feminist solidarity is an important activist concept. It is also an important fashion statement that draws our attention to fashion’s supply chains.

September 2016, for example, saw the debut collection by Dior’s first female artistic director – Maria Grazia Chuiri – at Paris Fashion Week. This included a £690 white slogan t-shirt that said ‘We should all be feminists’.

If you look online, there are much more affordable feminist t-shirts to buy that say:

Feminist [fem – uh – nist] – This is what a feminist looks like – We should all be feminists – Woman up – Women don’t owe you sh*t – You go girl – Smash the patriarchy – Strong Girls Club – The future is female – The future is feminist – Rebel girl – Ask me about my feminist agenda – Feminist AF – It’s my body, it’s my choice – Liberté, egalité, sororité – Well-behaved women seldom make history – This p***y grabs back – Fight like a girl – Sisterhood.

These t-shirts have been worn on catwalks, at protests and on charity telethons by celebrities including Cara Delevingne, Natalie Portman, Rihanna, Ariana Grande, Madonna, Eddie Redmayne and The Spice Girls. In these places, their messages can be empowering.

QUESTION: does a feminist t-shirt, by itself, create feminist solidarity?

TASK: to find the answer, read these two articles which make connections between the lives of women who wear and make feminist t-shirts in the global fashion industry. One t-shirt was hashtagged #IWANNABEASPICEGIRL and the other said This is what a feminist looks like.

QUESTION: according to these articles, what unequal power relations were faced by women working in the garment factories where these t-shirts were made? What contribution do they argue these t-shirts made to feminist solidarity in the fashion industry? How, and by whom, do you think a more truly feminist t-shirt be made?

EXTRA STUDY: any brand selling clothes with feminist messaging which doesn’t empower the women who make those clothes can be accused of ‘feminist-washing’ (or ‘purple-washing’). Similarly, brands selling clothes with positive LGBTQ+ messaging that don’t empower LGBTQ+ people who make them can be accused of ‘pink-washing’. Read how brands involve themselves in this ‘washing’, and how they can change the way they work to show feminist and LGBTQ+ solidarity, in this Elle Education blog post.

iii. Intersectional thinking

So, does this mean that only women can show solidarity with women, only LGBTQ+ people can only show solidarity with LGBTQ+ people, people of colour can only show solidarity with people of colour, disabled people can only show solidarity with disabled people, and so on? The answer is no. Simply because nobody is defined only by their skin colour, their body shape and size, their gender, their sexuality, their class, their age or their dis-ability for example. And because it’s possible to build coalitions across differences and systems of oppression and exploitation.

So, we need a more mixed-up understanding of identity and solidarity in which ‘race’, class, gender and other characteristics of our identities, and the disadvantages and discriminations that can accompany each of them, are seen to intersect. This is called intersectionality. Manifesto point #5 is all about intersectional thinking and intersectional acts of solidarity. So let’s examine this concept more closely.

TASK: watch this video which explains origins of the concept of intersectionality and its importance for environmental and social justice activism.

TASK: Think back to what you learned in the previous modules about who makes our clothes, where in the world, and who experiences the pollution from the many chemical processes our clothing material can go through before it’s ready to wear.

QUESTION: First, how would you describe the skin colour, body shape and size, gender, sexuality, class, age or dis-ability of the people who make and process the fabric for your clothes? Second, how would you describe your own skin colour, etc.? Then, ask yourself: who does this mean I can stand in solidarity with? a) only those people with the exact combination of characteristics that I have, b) anyone with whom I share one or more of these characteristics, and/or c) anyone with whom I share other characteristics like ethics, values or politics (e.g. in relation to climate change or sustainability)? What do you think?

FURTHER STUDY: to find out more about the importance of intersectional thinking about ethical and sustainable fashion, read these blog posts: ‘There is no ethical fashion without intersectionality”, ‘Intersectional environmentalism – what does it mean for the denim industry?’ and/or ‘Why the Fashion Revolution must be intersectional’.

iv. Intersectional solidarity

Next, we want you to think about how the concept of intersectionality solidarity can be put into practice in the worlds of ethical and sustainable fashion activism. There are two things to understand here: first, how marginalised groups can become empowered so that their ideas and perspectives can shape this activism; and, second, how solidarities in this activism can be built across lines of ‘race’, gender, class, language, and more besides.

TASK: To examine how intersectional solidarity can work, we want to watch a video of a fashion show which took place in Phnom Penh, Cambodia in May 2014.

QUESTION: Why did this fashion show take place? What events provoked it? Who modelled the clothes? What were their day jobs? What brands were they modelling and why? What were their demands? What scenes did they re-enact on the runway and why?

TASK: this show resulted from intersectional solidarity between garment workers and a number of different organisations who supported their demands and activism. Please read the following paragraphs and answer the questions that follow.

This fashion show took place at the headquarters of a Cambodian NGO called the United Sisters Alliance. One of its four members is an NGO called the Worker’s Information Centre (WIC) which had been campaigning for a living wage for garment workers in the country for some time. The WIC was established by workers for workers to help young women employed in Cambodia’s garment factories understand and stand up for their rights. The WIC runs drop-in centres where women can give each other advice and support, get healthcare and legal advice, and decide how they can act collectively to change their lives for the better. At the time of the show, the WIC was a partner organisation of an Australian NGO called the International Women’s Development Agency which funds women’s rights organisations in Asia and the Pacific region. It was also a partner organisation of a South Africa-based international human rights NGO called ActionAid which works with women and girls living in poverty. It had also received funding from an American NGO called the American Jewish World Service which supports social justice organisations in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean.

The show was designed and performed by garment workers living in Cambodia’s capital city, Phnom Penh. One 22 year old worker called Lin Na, said “I’m wearing the brands to show the buyers that their clothes are made by us. I want them to understand the link between the clothes I make and the garment workers’ situation and our salaries”. The fashion show was filmed and posted online by Canadian photojournalist Heather Stillwell and viewed by tens of thousands of people around the world. Chrek Sophia of the WIC explained its purpose, “We wish to inform [consumers] … to know about the Cambodian garment workers’ situation and take part in holding the brand companies accountable” (see followthethings.com).

QUESTION: Using this example, how did a marginalised group in the fashion system become empowered so that their ideas and perspectives could shape fashion activism? Who were this group and what were they able to do? How does this activism seem to have been helped by intersectional solidarities between and across lines of ‘race’, gender, class, language, faith, and more besides? What characteristics and interests did they seem to share? What differences did they seem to have? What information would you need to know to better answer these questions?

v. Reflection

Manifesto Point #5 imagines a fashion industry whose successes are not based on exploiting differences but are rooted in diversity, inclusiveness, solidarity and democracy. So, in the first part of this module, we asked you to consider if the diversity of people who buy clothes matches the diversity of people who design, model and make clothes. The answer to this question, at least in the worlds of fast and high fashion, seems to be a resounding NO. We asked if and how you would know that an item of clothing that said something about your politics – like a feminist slogan t-shirt – was performative or genuine. The answer was out of sight, along its supply chains, in the work and lives of the people making those clothes. And, to work together to challenge the inequalities and exploitations upon which the fashion industry is based, we asked you to think about how you might act in solidarity with garment workers who are similar to you in some ways, and different in others.

TASK: at the end of her article on ‘Why the Fashion Revolution must be intersectional’, Taneshia Atkinson suggests four ways that you can get involved ‘if you are in a position to do so’:

a) ‘Decolonise your wardrobe and buy from ethical and Black-owned brands’;

b) ‘Call out the lack of diversity in the fashion industry from leadership roles to designers, models and board members’;

c) ‘Listen to and amplify Indigenous voices. Indigenous people worldwide are the original land caretakers, life givers and matriarchs of sustainability’,

d) Use your digital activism. Ask the brand #WhoMadeMyClothes and #WhatsInMyClothes and don’t underestimate the power of writing to your local member of parliament.

We would like to add one more:

e) Volunteer your time and/or money to a workers rights NGO where you live. Find out which projects they support where in the world. Find out about their events and go along if you can.

QUESTION: Which, if any, of these options are you in a position to act on? As you have been working your way through this part of the course, what ideas and examples have popped into your mind? What do you already know about? What are you already doing? What could you search online to find more about?

You can express your thoughts and plans in any way you like: writing, sketching, photoshopping, whatever works for you!