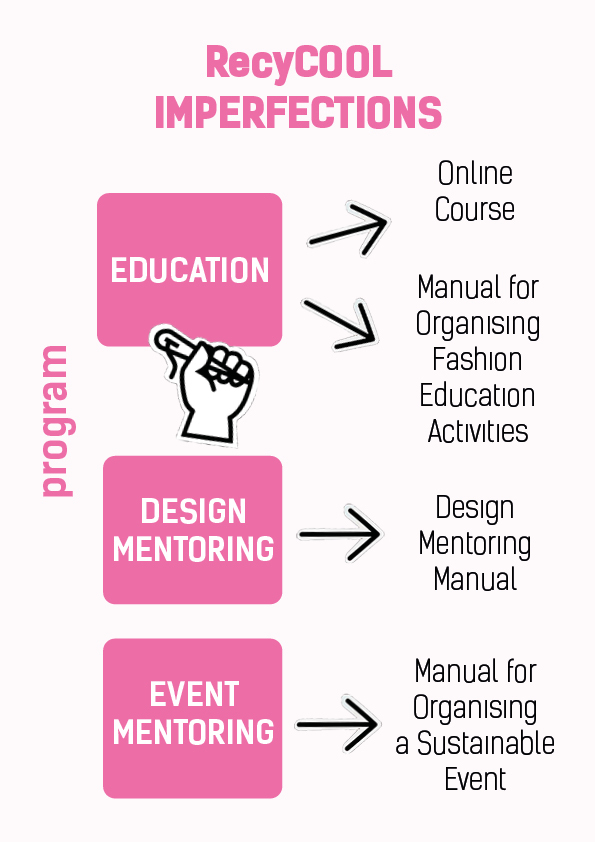

Module 4 part b

Living wages

We finish this module by looking closely at Fashion Revolution’s manifesto point #2. It pictures a time when the wealth that the fashion industry generates is spread more evenly among the people and communities who generate it.

QUESTION: How close do you think we are to this now? What do you think? Write down your thoughts.

Nobody who knows anything about fashion’s supply chains, and nobody who has been taking the course, would be surprised to hear that garment workers are paid poverty wages and constantly demand that they are increased. It’s also well known that when brands’ and retailers’ manufacturing costs (including wages) go up in one country, they can easily move their production to another country where these costs are lower. Each country sets a minimum wage level for its workers. But these wage levels are not always adhered to, especially when brands’ and retailers’ orders are outsourced by the factories who have been contracted to make them. And minimum wages are the lowest wages that can be paid by law. They are not the wages that people can necessarily survive on. Below, we will introduce you to a higher wage that’s called a ‘living wage’, the lives it can help garment workers to live, and the wider benefits for the societies in which they live. We ask who could pay for these wage increases? The answer is not only the consumers of those clothes…

We start this journey into living wages by looking at the price of a typical t-shirt, and thinking about where the money goes and how much it might cost to pay the people who made it a living wage. One option would be to increase the price of that t-shirt to pass on the cost of that living wage to its consumers, But, in our next task, we wonder who else could pay for a living wage by turning our attention to the extremes of wealth and poverty in the fashion industry. Here we contrast the wealth and lifestyles of billionaire fashion CEOs and garment workers and wonder if and how that wealth could be more fairly distributed. Next we take a closer look at what is meant by a ‘living wage’, what kind of living it can help to pay for, what it can be like for garment workers to earn less than this, and how the industry’s poverty wages can be justified. We finish the module with some final reflections. How can we help to create a more just and sustainable fashion industry by acting, not only as consumers, but as citizens? What powers do we have to encourage the change that is needed?

i. Where does the money go?

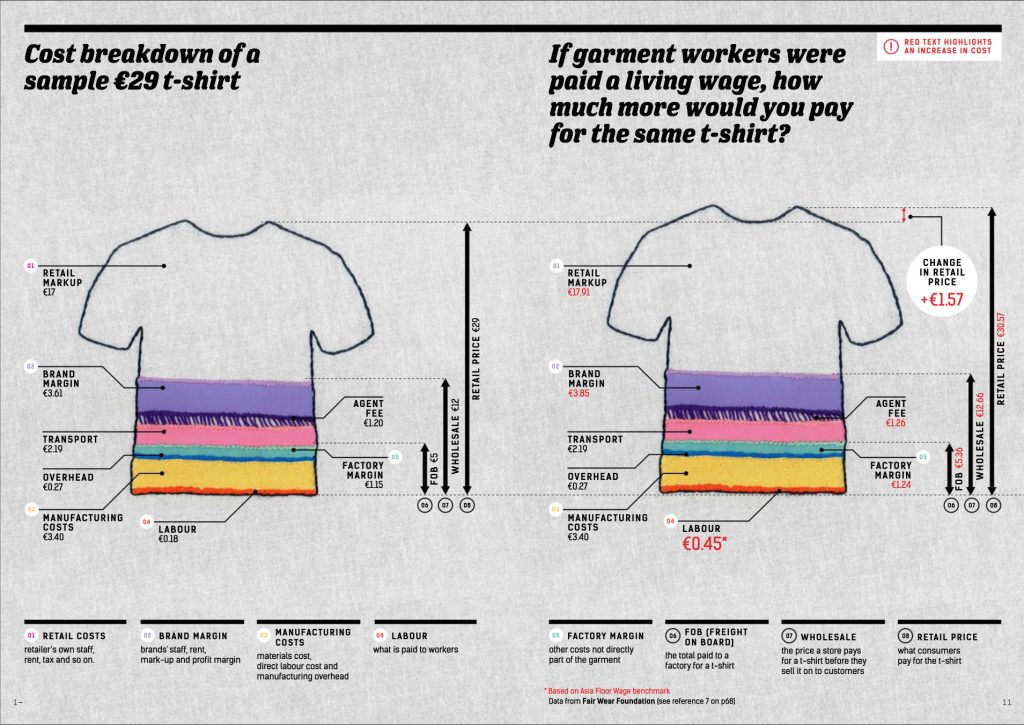

Imagine you’re at the checkout of your favourite clothing store. You are making a contactless payment for a new t-shirt. €29. Beep! You stop for a moment and wonder. Where does that €29 go? What are you paying for? What percentage of that cost pays the wages of the people who made it? How much would the price need to increase for those people to make a living wage?

TASK 1: Take a careful look at these diagrams taken from Fashion Revolution’s 2017 fanzine Money Fashion Power (p.13).

QUESTIONS: How much would the retail price of a €29 T-shirt have to increase for the people who made it to earn a ‘living wage’? Would you be happy to pay that extra if you knew into whose pockets it went? Should it be you, as a consumer, who pays more? Could other people pay these workers these higher wages?

ii. Extremes of wealth and poverty

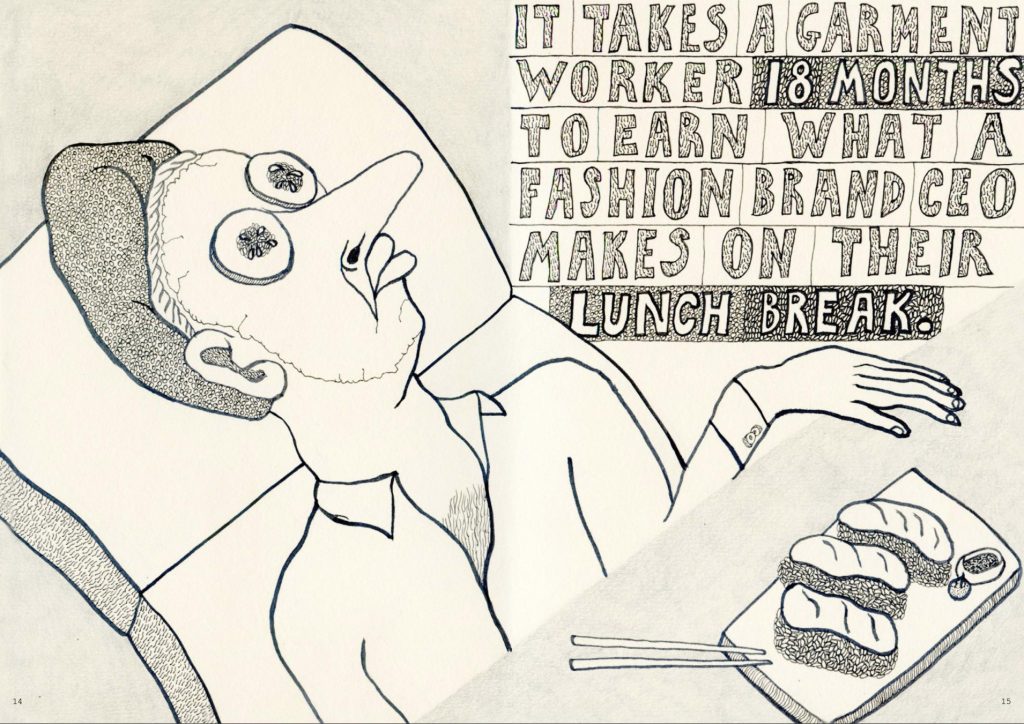

Later in that fanzine there’s an illustration which compares garment workers’ wages to those of the CEOs of fashion brands.

Fashion Revolution believes that it’s not only consumers who might need to change their ways to create a more just and sustainable fashion industry. Not everyone, for example, can afford to pay more for their clothes. So, in this section, we look away from the fashion industry’s poverty to look at its most extreme wealth.

Each year the American business magazine Forbes publishes a list of the world’s richest people. In 2023, its top 40 included a number of people who have made their fortune from the fashion industry. So, let’s learn something about the two richest fashion billionaires – Bernard Arnault and Amancio Ortega – and then contrast their lives and lifestyles with that of a garment worker living in Vietnam called Lin.

TASK 1: Read the two paragraphs below about Bernard Arnault and Amancio Ortega. Each one is followed by a brief summary of a recent newspaper exposé from their company’s supply chains.

QUESTIONS: Can you imagine making and spending this much money? What would you do with it? How would you use it to take care of your family? Who would you spend time with? Why would they want to talk to you? Whose money would you think you were spending? How, and by whom, was that wealth generated?

Bernard Arnauld and family were Number 1 in the Forbes 2023 list with a net worth of US$ 242 billion. Arnault is the 74 year old founder, chairman and CEO of the French luxury goods conglomerate LVHM (Luis Vuitton Moët Henessey) whose fashion brands include Louise Vuitton, Celine, Dior, Fendi and Marc Jacobs. According to the Business Insider website, hanging on the walls of his home on Paris’ Left Bank are original artworks by Pablo Picasso, Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Damien Hirst. He has five children, all of whom work for LVHM. His daughter Delphine, for example, is heir to the LVHM empire and lives with a tech billionaire and her daughter. His son Antoine is CEO of LVMH’s holding company Christian Dior SE and is married to a supermodel. Arnault owns a US$150 million eco-friendly superyacht that costs US$10-15 million a year to run and travels everywhere by private jet. He owns a sprawling vacation villa on the French Riviera and enjoys playing tennis. He owns property in Hollywood and Beverly Hills. He has met President Trump at Trump Tower in New York. President Putin met him at a French chateau owned by LVHM. His friends include former French president Sarkozy and former Apple CEO Steve Jobs and he has partied with Princess Diana. In January 2019 he is said to have made US$4.3 billion in a single day when the value of his shares in LVHM went up by 6.9%. In the 12 months before he rose to the top of the Forbes list in 2023, his wealth grew by US$53 billion. His rise to the top, one journalist wrote, came “through hard work and a certain creativity to become the undisputed master of the luxury goods universe”.

In March 2020, the New York Times published a story called ‘Luxury Fashion’s Hidden Supply Chains’, which found that “embroiderers [subcontracted by LVHM suppliers] completed orders at unregulated facilities that did not meet Indian factory safety laws. Many workers still do not have any employment benefits or protections, while seasonal demands for thousands of hours of overtime would coincide with the latest fashion weeks in Europe”.

Amancio Ortega was Number 14 in the Forbes 2023 list with a net worth of US$84 billion. Ortega is the 86 year only founder and former chairman of the Spanish Inditex fashion group, the world’s largest clothing retailer whose brands include Zara, Bershka, Massimo Dutti and Pull and Bear. Inditex has over 4,000 stories in 96 countries and its e-commerce site is one of the world’s largest. According to the Business Insider website (2023, link), he used to spend time at Zara’s headquarters sitting with designers and fabric experts, and eating with his employees in their cafeteria. When his first wife, and co-founder, died in 2013 their daughter Sandra inherited her wealth and became Spain’s richest woman. Marta, his daughter with his second wife, became Inditex’s chairwoman in 2022 and is married to a modelling agent who is the son of a fashion designer. He built an equestrian centre near La Coruna because Marta is a competitive show jumper. He put his US$84 million superyacht Drizzle up for sale in 2022. Much of his wealth is invested in real estate in Madrid, Miami, London, New York, Chicago and Washington D.C. He earns around US$400 million a year from his shares in Inditex and other companies and has successfully hidden from the media spotlight for decades. His “success story,” according to one fashion website, “is an inspiration to many, and it shows that with hard work and determination, anyone can achieve great things”.

During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, a factory making Zara clothes in Myanmar laid off over a hundred workers who had been earning US$3 a day for a six day week. These workers said that Zara’s supply chain relied on union busting because those dismissed were all members of a recently formed trade union.

TASK 2: Watch this 3 minute video in which Lin, a garment worker from Vietnam, talks about her work, pay and children.

QUESTIONS: Can you imagine making and spending the money that Lin earns? What could you do with it? How could you use it to look after your family? Who could you spend time with? Why would they want to talk to you? Whose money would you think you were spending? How, and by whom, was that wealth generated?

TASK 3: Let’s finish this section by comparing these extremes of wealth and poverty by doing some simple maths.

QUESTIONS: if Lin works 7 days a week, 52 weeks a year and earns US$1 dollar a day, how many years will it take her to earn US$242 billion? After you work this out, to what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statement?

“What is very transparent to us all, is that a lot of CEOs who make missions have, in very simple words, stolen. Truly, it’s not that the CEOs made this money, the money has been made by child workers in the supply chain that do the work. CEOs steal women’s lives when they pay them poverty wages, to fulfil their own ego. And this is very immoral work. … So now it is time for these companies to open their hearts and provide a living wage. And I know you can still make millions. You don’t need to make billions”.

Nasreen Sheikh – former garment worker in Tibet

FINAL QUESTION: Do you think that increasing the price of clothes is the only way that garment workers can earn a living wage? Go back to the t-shirt diagram and think where else that money could come from.

EXTRA STUDY: to find out more about how the super rich get, and stay, super rich, and how their wealth can and should be redistributed, see this 2023 report by Oxfam called Survival of the richest: how we must tax the super-rich now to fight inequality.

iii. What can you buy with a living wage?

A 2022 survey by Fashion Revolution of 250 of the biggest global fashion brands found that 94% of them published no information about their progress towards paying living wages, and 96% published no information about the number of people working in their supply chains actually being paid a living wage. In this section, we will look in a little more detail at the difference a living wage can make to garment workers’ lives, and then try to find that tiny percentage of brands who pay that wage. If they can, so could others!

TASK 1: Take a look at this infographic published by the Clean Clothes Campaign about what a living wage means you can afford.

QUESTIONS: How many of these seven things can you afford and/or are given to you for free? Imagine not being able to afford all of these things after you put in the kind of hard work, all the hours, 6 days a week, that Lan describes.

TASK 2: Next, take a look at the Clean Clothes Campaign’s Fashion Checker website and scroll down to the section called Living wages not poverty Wages. Click the boxes for food, rent, etc. in the left (minimum wage*) and the right (living wage) columns and compare what they say.

* the minimum wage is the lowest wage that someone can be paid by law. It varies from country to country.

QUESTIONS: What do you think about these contrasts? What difference can a tiny transfer of wealth from minimum to living wage make to the lives of garment workers?

TASK 3: Next, let’s think about the pressure that could be put on brands to pay ‘living wages’. It’s clear that they are not going to pay this voluntarily. If one brand chooses to pay a living wage throughout their supply chains, what will happen to their sales if their competitors don’t also so this? To understand this process better, we’d like you to watch the last 7 minutes of Livia Firth’s 2020 film Fashionscapes: a living wage. It starts with her talking about what fashion brands ‘normalise’…

QUESTIONS: Why do the people in this film believe that new European Union legislation has a better chance of making things happen? What would make brands pay a living wage? Imagine you are writing a play about the global fashion industry. There’s a scene in which Bernard Arnault (or Amancio Ortega) meets Lin and they compare the opportunities they have been able to give to their children. How do you think he would justify the differences? How do you think he would explain why she couldn’t be paid a living wage?

EXTRA STUDY: see how Cambodian trade unions negotiated for higher wages in 2022 based on a survey of garment workers’ daily spending needs, and the pay rise they were awarded. Whose help do they ask for in this video?

EXTRA STUDY: search online for fashion brands who pay workers a living wage. What can you find?

iv. Reflection

We finish this module by asking a simple question: could paying fashion’s supply chain workers a living wage make good business sense? Is it only good for those workers, or could there be wider benefits? A recent Cambridge University research paper lists 16 benefits of paying workers a living wage. If people are paid well enough to live on, for example, they will be healthier and won’t take so many days off sick, they are likely to be more committed to their work, and to change jobs less often which means that less time and money is needed to recruit and train new people. A more stable and satisfied workforce can mean less time and money has to be spent on managing ‘labour issues’ including, for example, workers striking for higher wages. People who are paid a living wage can spend more money in their local communities, which provides opportunities for other people’s businesses to thrive. And thriving economies can mean fewer people will be driven to leave their home countries in search of higher paid work.

In this module, we have looked closely Fashion Revolution’s Manifesto points #3 and #2, which picture a future fashion industry in which garment workers have a voice, speak without fear, and can negotiate for better working conditions which include living wages. The title of this module is ‘Good clothes, fair pay’. We have taken this from an NGO campaign that gives people living in the EU an opportunity to change the fashion industry for the better not as consumers, but as citizens. Watch this short video which explains how:

QUESTIONS: Have a look at the Good Clothes Fair Pay website, and consider signing its petition (if you are an EU citizen). And then think. Knowing what you now know, how can you best use your power, your wealth, your influence to make your contribution to a more just and sustainable fashion system? Has your answer changed? From what to what? How much of a revolution is the Fashion Revolution?

Please express your answers in any way you like: writing, sketching, photoshopping, whatever works for you!