Module 5 part a

Circular fashion

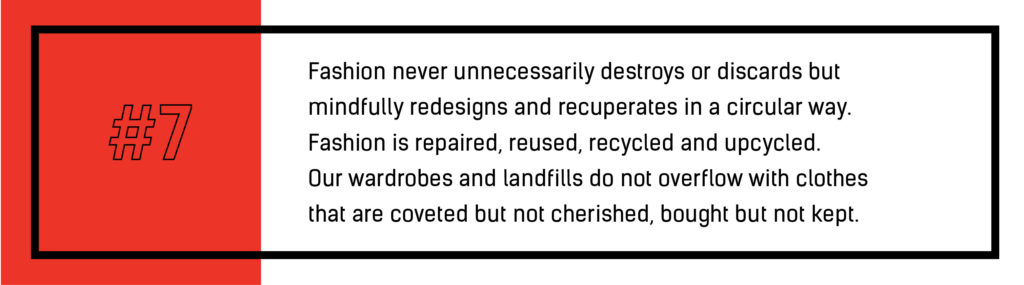

In this final module, we start by looking closely at a concept we briefly introduced in Module 2b – the circular economy – and one way to hack the system – mending, repairing, wearing many many times a smaller number of clothes – because loved clothes last. So let’s start by reading Manifesto point #7 more closely.

QUESTION: How close do you think we are to this now? What do you think? Write down your thoughts.

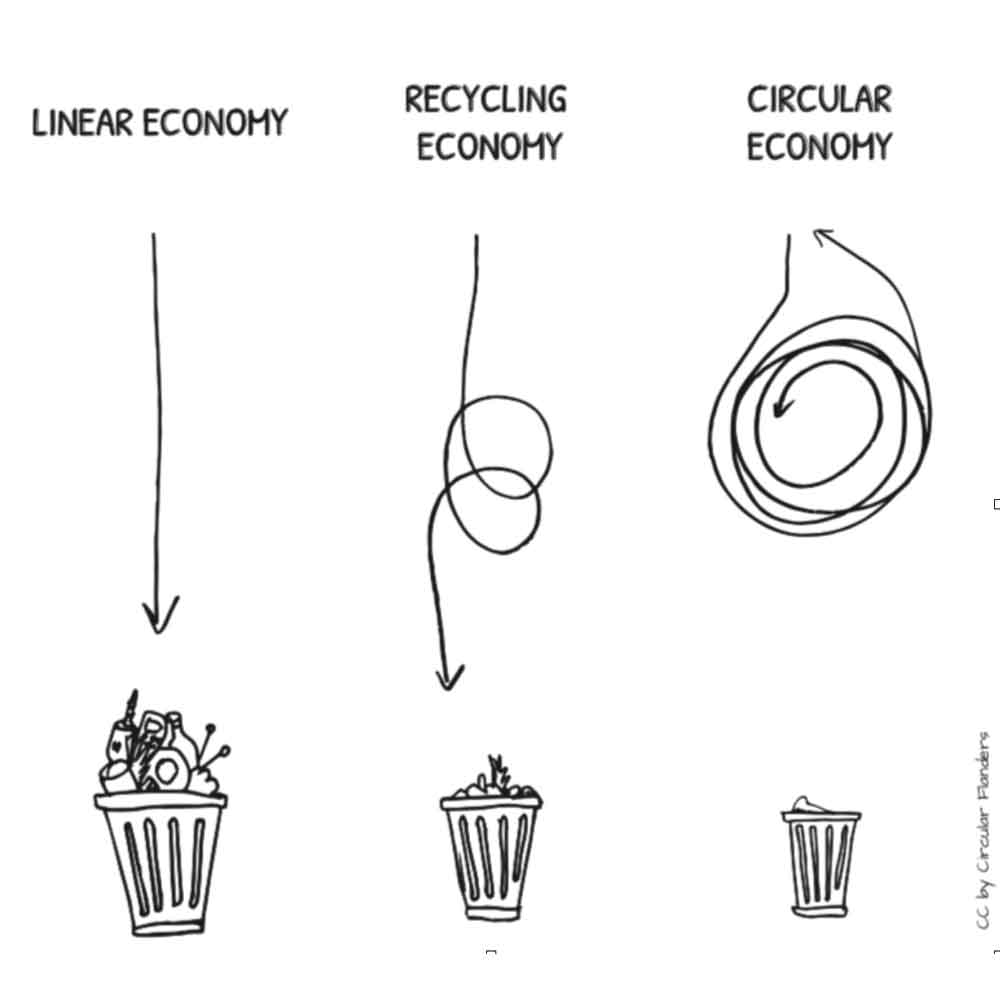

The concept at the heart of this manifesto point is ‘circular fashion’. In Module 2b part ii), we looked at the fast and ultra-fast business models of fashion brands like Zara, H&M, ASOS, Boohoo and Shein. These fast fashion models are all forms of linear economy in which new clothes are constantly manufactured in the knowledge that they will end their lives as waste (e.g. incinerated or dumped in landfill). As the diagram below suggests, a recycling economy modifies a linear economy by, for example, extending the lives of these clothes, but they also – eventually – end up as waste. A circular economy is completely different because it produces – in theory at least – zero waste.

The ‘circular fashion model’ is currently a hot topic in the industry, with brands like H&M, Inditex (Zara) and VF Corporation (whose brands include Vans, North Face and Timberland) taking part in circular fashion initiatives. So, to better understand manifesto point #7, our aim below is to understand and question what they are getting excited about.

i. Waste in fashion’s supply chains

As the diagram above shows, the circular fashion model avoids the ‘waste’ bin. Waste is “unwanted matter or material of any type, especially what is left after useful substances or parts have been removed” and “a bad use of something valuable that you have only a limited amount of” (Cambridge Dictionary). So let’s look at how much waste is generated – and where – in fashion’s linear supply chains.

There are two types of waste in the fashion industry: i) pre-consumer waste – which is generated in supply chains before clothes are sold; and ii) post-consumer waste – which is generated by consumers who will, at some point, need to get rid of clothes that they have bought. As consumers, many of us believe we have a responsibility to think about where this waste should go and how to minimise it by buying less, choosing well and making it last (as discussed in Module 2b). Earlier in this course, we discussed chemical and other waste (also known as pollution) that is generated in the production of cotton and in the making of fabric (see Module 2a).

TASK 1: Go back to the information in Module 2a and 2b about the waste generated in these two parts of fashion’s supply chains.

QUESTIONS: What chemicals and other substances help to make your clothes, but do not remain in your clothes (e.g. enzymes, plus what…)? What substances do these processes take away the raw materials that make up your clothes (e.g. wax, plus what…)? Make a list which includes where you think this waste might go and who has to live with it.

This is just some of the waste generated in the making of clothing materials. Once these materials are made, they can also become waste. This is what we’re looking at next.

TASK 2: Read this quotation from fashion designer Phoebe English who describes the first stage of the process through which rolls of fabric are turned into clothes.

QUESTIONS: Look at the clothes you are wearing right now and imagine the ‘spaces around’ them. Imagine the shapes of the ‘cutting waste’. Draw on a piece of paper the shapes of the panels which were stitched together to make one item of your clothing. Arrange them on the page to minimise the cutting waste. How much is there?

“For those of you who are not familiar with the production process of a garment, you have your flat fabric laid out on the table, you have your pattern pieces – your sleeve piece, your front piece and your back piece – you lay them on the fabric, you cut around your pattern piece, you get your garment pieces and you put them together, but you are left with waste fabric. If you imagine every shop on Oxford Street and every garment that is hanging on a hanger in those shops … then imagine that the space around that garment, every single garment, is waste” (in Fixing Fashion 2019).

TASK 3: This ‘cutting waste’ is just one element of material waste in fashion’s supply chains. So, next, let’s look at the table below to see what some other forms of material waste are.

Textile industry waste (making fabric)

- Cotton lint

- Damaged yarn

- Fly fibre [flecks that break off and hang in the air]

- Greige fabrics [fabric that hasn’t been fully bleached or dyed]

- Rejected fabrics [e.g. their colour is not right]

- Excess finished fabrics [more than they can sell].

Garment industry waste (making clothes)

- Cutting waste [TASK 2]

- Excess production [more than they can sell]

- Defective clothes [every item has to be identical!]

- Rejected clothes [order that are returned for some reason]

- Cancelled shipments [orders made but never reaching the shops].

Adapted from Cleaner Environmental Systems

QUESTIONS: Looking at this table, which pre-consumer fashion waste do you think could be reduced or eliminated? Which pre-consumer fashion waste could be made and sold as garments? What would you think if, in a rack of supposedly identical garments, you found individual garments with slight flaws and differences?

EXTRA STUDY: in 2018, the British fashion brand Burberry reported that it has destroyed £28.6m worth of its unsold clothes, accessories and perfume. Find out why here, and what the company’s response to criticism of this action encouraged them to do here.

ii. The circular fashion model: in principle

So, how could the fashion industry work differently to minimise or eliminate waste from so many points in its supply chains? The answer, for many, is to move towards a circular fashion model. This is the model in the diagram above where nothing ends up in the bin.

TASK 1: Watch this 2 minute video from the Ellen McArthur Foundation (2018) which explains how this circular fashion model is supposed to work.

QUESTIONS: What seems new and different in this circular fashion model? What kind of thinking, and what kind of technology, is important for it to work successfully? How does it avoid creating the waste that fashion’s linear model creates?

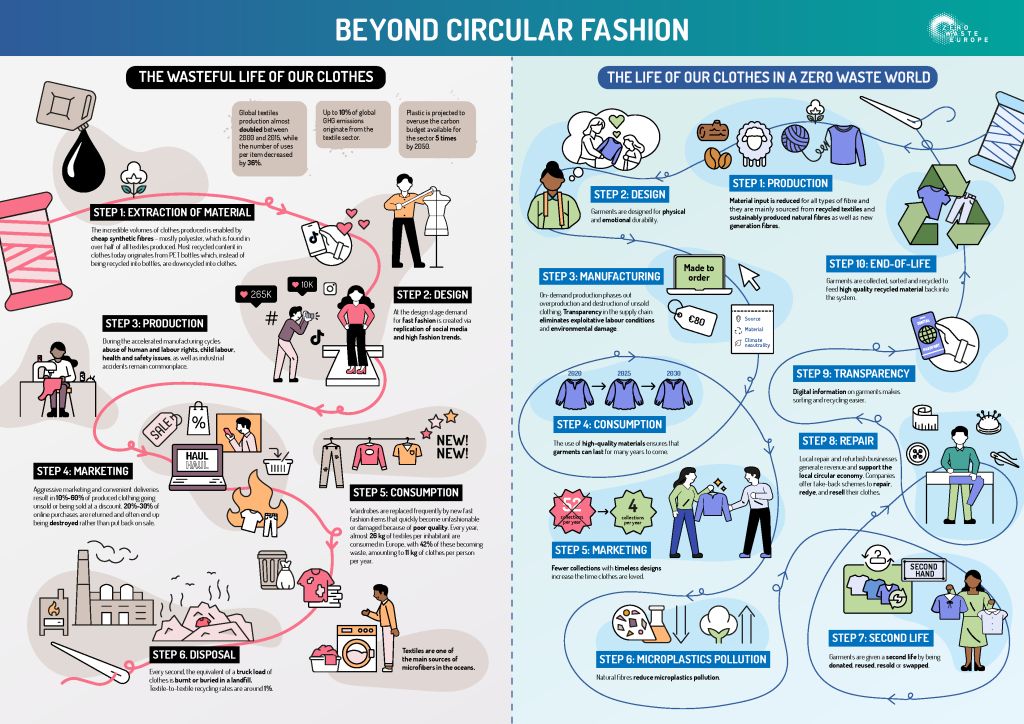

TASK 2: To understand the differences between fast/linear and circular fashion, start at Step One of the infographic below and follow the life story of a linear (left) and a circular (right) garment.

QUESTIONS: List the main differences you can see between the lives of these two garments. Where are these differences taking place, how, and who is involved in making them? How is circular fashion different for its consumers? How does it seem to be different for its textile and garment workers? Where do they appear? [we will return to this last question later]

iii. The circular fashion model: in practice

The circular fashion model has been around for some time now, and is beginning to be put into practice. We can learn a lot about its potential from the companies that are trying to work according to its principles. This is where we introduce a circular economy charity called the Ellen McArthur Foundation.

TASK 3: Watch this 10 minute 2 video playlist. The first video follows a journalist who visits the headquarters of the Ellen McArthur Foundation to hear more about the circular fashion model, and then visits some clothing companies which illustrate how it can work in practice. In the second video, we hear from the brands who won Ellen McArthur Foundation awards in 2022 and find out how they contribute to the circular fashion economy in different ways.

QUESTIONS: How does the circular fashion model already seem to be working? What are circular clothes like? What can you buy? What can you, and the companies that make them, do with those clothes after you finish with them? What can happen to them? Where can they go? Have you seen circular clothes in store or online where you live? What seems attractive and affordable to you?

iii. Putting thought, and work, into our clothes

What is perhaps most interesting about the circular model of fashion is that the role of ‘the consumer’ is no longer to buy, wear and bin clothes on a regular basis. That’s fast fashion’s linear model of consumption. In the circular model, the person who buys clothes is – according to fashion theorist Kate Fletcher – their user and their crafter. Users and crafters buy fewer clothes, put lots of thought, work, love into them and therefore want to make them last. The thrills of shopping and keeping up with the latest fashions are replaced by different, equal thrilling activities.

TASK 1: Watch this 12 minute TED talk in which Kate Fletcher explains the ‘craft of use’: the project where she talked to 500 people around the world about the clothes that they love.

QUESTIONS: What does Kate Fletcher mean by the ‘craft of use’? What does it involve? Are you already doing this, at least a little bit? How does it rework the thrills of linear fashion consumption? What thrills does it offer instead? Why are these alternative thrills essential to the circular fashion model? What does the model expect of its consumers?

TASK 2: Many people have the skills needed to clean, repair, adjust or rework clothes that they once loved but don’t wear any more. Many can ask or pay people who do. Many do not. And many can learn. In this task, we want you to find an item of clothing that you have loved, kept, but no longer wear. We want you to find and learn some skills – and maybe a different attitude – to bring it back to life.

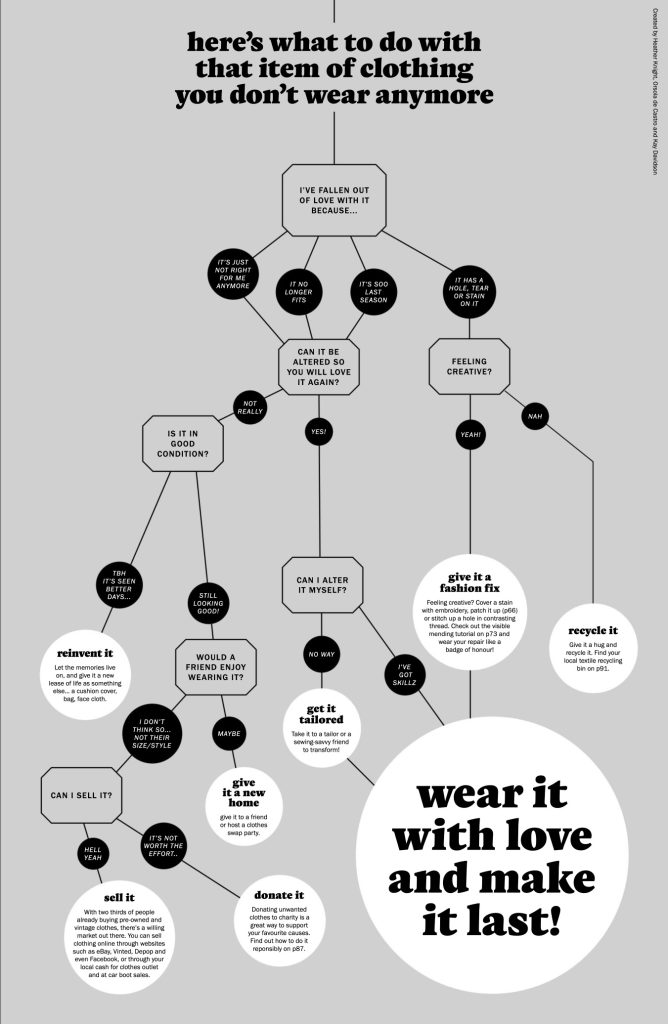

QUESTIONS: What’s stopping you from wearing this? Have you outgrown it? Is it ripped, faded, stained, the wrong colour? Has a button fallen off? Have moths eaten a hole in it? Why have you kept it? Take a look at the flowchart below. Where does it take you and that item of clothing? How can you help to prolong its useful life?

EXTRA STUDY: this flowchart is taken from Fashion Revolution’s Loved Clothes Last fanzine. Find out more about the options it presents by reading the whole thing here.

iv. What about the garment workers?

The linear model of fast fashion is the model that we are living with today, the one we have been studying in the course, the one whose farmers and factory workers we have been thinking about the most. In this task, we ask what this circular fashion model might mean for them. This model insists that fewer – but higher quality – clothes should be made new, and that more effort should be put into making those clothes last and into recycling their materials once their useful lives are over. We have seen glimpses of the new kinds of work that this circular model will require – e.g. machinists sewing offcuts of denim to make fabric, recycling workers being able to take circular shoes apart to recycle their parts, or chemical processes that can recover cotton and polyester fibres from discarded clothes.

So, our next task is to ask what happens to the garment workers in this circular fashion model? One criticism of this model is that it pays little or no attention to this question. In 2019, the Institute for Development Studies asked whether the circular economy model “is truly embracing the … opportunity it has to not only redesign the system to reduce waste, but also design out poverty and inequality” (Circular Garments: what about the workers? 2019)? So let’s look into this.

TASK 1: To answer this ‘what about the workers?’ question, they took the five circular fashion recommendations in an Ellen McArthur Foundation (EMF) report called A New Textile Economy and responded to them one by one. For this task, we would like you to read these recommendations and responses and think about the questions that follow.

Recommendation 1: “Change how consumers buy and engage with clothes, focusing on: short term rental, subscriptions rental, sale of highly durable clothes, repair and resale of clothes.”

Response: “This is likely to mean fewer clothes being produced, and thus less demand for garment workers with their skills needed elsewhere (e.g.: within repair and resale of clothes). Or, the industry could keep the same number of workers, but produce fewer, but high quality and durable clothes with workers under less pressure.”

Recommendation 2: “Change how we use and create textiles, using less environmentally damaging textiles … and diverting waste fabric from landfill by turning it into new items.”

Response: “This has the potential for new employment opportunities for workers within the upcycling of waste-fabric, however, outside of the garment factories, there could be issues relating to working conditions for those involved in making the materials.”

Recommendation 3: “Phase out substances of concern meaning clothes create less toxins, natural materials could be composted after use, and less toxins in landfill.”

Response: “For workers, a large benefit would be improved health with reduced exposure to toxic substances, as well as positive implications for communities in the vicinities of textile manufacturing sites (e.g.: reduced water pollution).”

Recommendation 4: “Use technologies that facilitate reuse and recycling of clothes – for example, technology that can unravel yarns, and … sort garments for reuse / recycling based on colour and material.”

Response: “If the garment sector takes the high-tech path, production may shift to places with a higher skilled workforce. There would still be a need for garment workers in current production sites, but potentially fewer of them and they would need to be up-skilled to handle technologies. There is also a risk that a new cohort of workers are introduced to manage the technologies, rather than absorbing the existing workforce.”

Recommendation 5: “States to implement Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), meaning the end-of-life stage of a garment becomes the responsibility of the brand (implementation of EPR is already being done by the EU, and the UK’s recent Environmental Audit Committee Report is recommending the Penny Tax as a form of EPR).”Response: “EPR policies would not directly impact garment workers in current supplier countries but would require new reverse logistics operations, and it would need a workforce to sort and recycle garments closer to consumer markets. It will be important to ensure safe and decent working conditions for garment collection and recycling workers.”

QUESTION: What seem to be the pros and cons of the circular economy for garment workers? Is it likely the number of garment workers will increase or decrease as we move to a circular fashion model? Might these garment workers need the same skills or different skills to make a living? Could their jobs have the same pay, status and protections? Is it likely that the number of people needed in fashion’s new circular economy jobs will increase? Are these jobs likely to be in the same or different countries as they are now? How much of a shake-up could a transition to a circular fashion economy cause?

TASK 2: In 2021, an organisation called Business for Social Responsibility asked this ‘what about the workers?’ question to brands, unions, workers and other ‘stakeholders’ in fashion’s supply chains (Keeping workers in the loop 2021). Their report is detailed and thought-provoking. In this task, we focus on what it says about how a circular fashion model in India could decrease the number of garment factory jobs and increase the number of waste collecting jobs. The report tells the story of an Indian woman who left a job in a garment factory to collect garment waste. We would like you to read her story below – and the reports’ wider concerns about this – and answer the questions that follow:

A waste collector’s story:

“I started out sorting clothes. We’d get these giant bundles from all over the world, but all the good stuff had already been picked out by their sorters for resale. What was left was for recycling or downcycling. We’d have to sort through it based on colors, content, and making sure any trimmings were removed. Slowly our work got easier as machines came into help us, but there was also just less work. First, they could separate the colors, then as the brands started using new labels and they brought in new chemical recycling systems and suddenly sorting for content was gone too. Eventually, there were fewer and fewer sorters needed. I was pregnant when all the major cuts were made, and I was passed over for training to stay on as a system supervisor. It was a very dark time for me as I was a new mother and had no access to unemployment benefits, childcare, and all that. Eventually I found new work in collecting old garments. I knew a fair share about clothing content from my days as a sorter, so I was quite good at it. There were also a lot of old garment workers starting to collect clothing too who were also good, so the competition was tough. The shift in the industries was quite a shock as no one seems to care if organizations follow the law in my new world as a collector. There are some bright spots though. As a waste collector I have a lot more flexibility to work around my childcare availability. I’m also now part of the “Connected Collectors,” which is a mobile app that helps me pre-sort clothing as I collect it, and helps me get a fair prices for my finds. My income has increased a lot since joining the app and I’ve also helped train other collectors onto the app. The system does monitor your “‘find rate” though, which can make taking a break to rest or spend time with my child feel stressful. I’ve heard from the community organizers from the app that the government is thinking about getting in a big company and machines to do our job at the landfill, and they plan to organize the waste better and even use some for electricity. I’m determined to not miss my chance at getting trained for another job again, so this time I am doing everything I can. Through the app we have access to a digital community of collectors and we’ve started organizing ourselves better. I’ve attended every meeting so far, and I’ve heard that there is a proposed “Mandatory Reskill for Recycled Content Program” coming from Europe, which means that brands that use our collected waste have to help us get new skills. Through our digital community, we’ve connected directly with the workers in Europe, and we’re all working together to help push the program through. I’ve already signed up for some technology training. I think my experience as “Connected Collector” trainer will help me. Plus, I’m optimistic since now that we only have work four days a week, work is meant to be shared more evenly.” (pg.73)

Business for Social Responsibility – Keeping Workers in the Loop

The report’s concerns

“Jobs in recycling will tend to increase, at least in the first stages of growing circular models. Historically, these jobs have been informal, dangerous, and offer low protection, particularly in lower income countries. The transition to circularity will expand the global fashion supply chain to include recycling vendors and waste collectors and add specific human rights risks in addition to those the industry currently struggles with (p.102 link).

“Current levels of harassment and discrimination, including violence against women, also pose an ongoing challenge to a just, fair, and inclusive transition to the circular economy. According to a worker representative in India, the pandemic has increased levels of harassment due to the declining number of available roles. This serves as an example of how disruptions to the industry can exacerbate the issue. Harassment and discrimination could also be worsened by the need to acquire new skill sets to access new roles leading to increased vulnerability of workers in the face of declining job availability. Further, we could see workers, particularly those with existing vulnerabilities including women and migrant workers, moving into more precarious roles in the industry, or in new industries altogether. Additionally, some of the roles expected to expand under a circular economy have historically faced high levels of discrimination and harassment. In India, recycling workers surveyed reported higher levels of harassment than garment workers. Waste pickers are known to face discrimination from broader society and harassment from law enforcement, and women waste pickers have historically experienced sexual and physical abuse from private security forces, law enforcement, and other workers” (p.92 link).

“Key stakeholders in India also highlighted the short working life of manual workers due to physical job strain. They emphasized the need for fair payment and working conditions because many of these workers in their 50s tend to move out of the jobs due to inability to do physical work. They also highlighted how the jobs for low-skilled women workers will increase soon for segregation and sorting roles because employers find women to be more skillful in these manual roles than male workers. This of course raises concerns about the quality of these future jobs and questions on the role of upskilling in the transition to circularity. A key informant working in recycling in West Africa suggested that the idea circularity is motivating the reskilling and upskilling of the most marginalized groups of workers is misleading because, in many cases, workers in the traditional garment industry are being trained to do lower skilled jobs than those they currently hold to be able toparticipate in the circular system” (p.100 link).

QUESTIONS: Does it seem likely that the transition from a linear to a circular fashion economy in India will simply involve workers moving from one kind of job to another? What does the story above suggest? How does it seem that garment workers, in India at least, stand to benefit (or not) from this transition? Should the circular fashion model include the same attention to labour rights, living wages, etc. that the linear fashion now includes? Do you think that brands investing in circular fashion initiatives – like H&M, Inditex (Zara) and VF Corporation (its brands include Vans, North Face and Timberland) – might be committed to these changing labour rights issues too? How would you find out?

v. Reflection

It seems that the fashion industry is currently testing out the possibilities of a circular fashion model. A number of well known brands are investing in initiatives and sometimes winning awards for doing so. A number of newer brands are designing their business models to make this model work. This model has lots of positive ideas and it’s exciting to see them already taking shape. And it asks all kinds of interesting questions and poses all kinds of interesting challenges for fashion’s consumers: not least how to channel the thrills of shopping for clothes into the thrill of caring for them. All of this seems possible, partly because many of us are already doing some of these things and/or know people who do.

So what is there to reflect on here? All the way through this course, we have shown the importance of Fashion Revolution’s central question: who made my clothes? We have shown how this question needs to be asked because the fashion industry has hidden from its consumers the exploitation of the workers who make the clothes they wear. We have looked at the kinds of connected struggles that are necessary for workers, consumers, and everyone in between to create a more just and sustainable fashion system. This module has added a twist to this by latching onto the industry’s fascination with the circular economy model as a sustainable reworking of the fashion system that pretty much everyone agrees is needed.

QUESTIONS: As the circular fashion model begins to take hold, let’s add another question to ask of the brands involved: who circulated my clothes? Going back to each example of the circular fashion brands and retailers like Rapanui, Brothers We Stand, Timberland, etc. in the videos above, are there any specific questions you would want to ask them about the workers in their supply chains?

Please express your answers in any way you like: writing, sketching, photoshopping, whatever works for you!