Module 3 part b

The right to dignified work

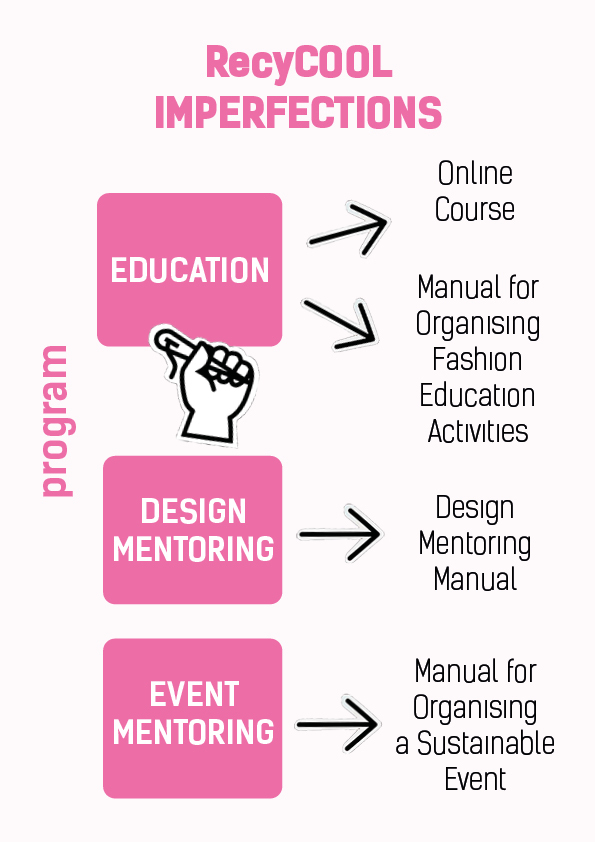

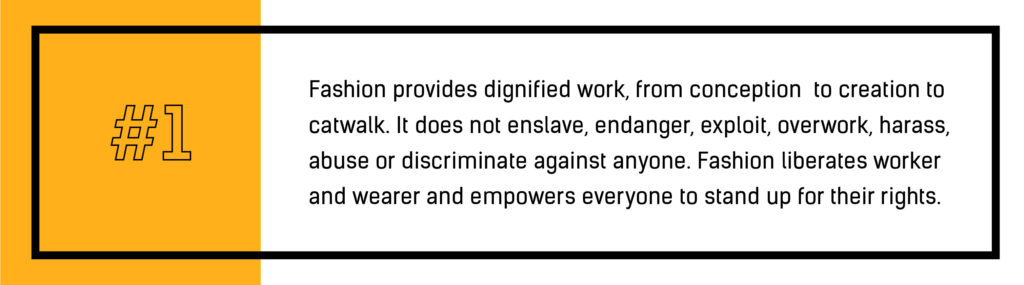

Let’s start the second part of this module by looking closely at Fashion Revolution’s manifesto point #1. It pictures a time when the fashion industry provides dignified work for everyone who works in it.

QUESTION: How close do you think we are to this now? What do you think? Write down your thoughts.

When we find out more about the environmental and social costs of fast fashion, so much of what we find can seem morally and ethically wrong. In the second part of this module, we will examine how it can also be illegal because garment workers have rights in international law. They have rights to decent, dignified work that doesn’t involve enslavement, exploitation, overwork, harassment, abuse or discrimination. But these laws are not always understood or put into practice in every workplace in every country. These rights can empower workers (and by implication wearers) but they have to be fought for, again and again.

Here, we take a look at what are called ‘universal human rights’, their history and their implementation worldwide, how they oblige states (or countries) to provide their citizens with paid work that can provide them and their loved ones with a dignified life; how worker’s rights have been internationally agreed and put into law, how they are implemented differently in the countries connected through the international fashion industry, and how they require constant vigilance, collaboration and activism so that they can continue to be enjoyed by fashion wearers and workers alike. We finish this module by asking how we can help to create the world that Fashion Revolution’s Manifesto imagines by thinking and acting not only as consumers but also as citizens, and also recognising that others can, and have to, think and act too.

i. What are human rights?

Manifesto point #1 wants there to be ‘dignified work’ in a fashion industry where everyone is empowered to ‘stand for their rights’. But what are these rights? We need a history lesson – about the UN’s 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).

TASK 1: Watch this 3 video playlist which includes two short Amnesty International videos about the UDHR and one short UDHR video about ‘Article 23’ on workers’ rights. As you watch them, please take some notes in answer to the following.

QUESTIONS: Why was it necessary for the UDHR to be written after the Second World War? How was it intended to unite people around the world? What are human rights and who, ideally, has them? Which of these rights seem to be relevant to people’s work?

ii. What are workers’ rights?

Next, we need to understand what ‘workers rights’ are, who decides them, how they are put into law, and how and where they are (not) implemented. Here, we need to introduce a United Nations agency based in Geneva, Switzerland, called the International Labour Organisation (the ILO). This is where worker’s rights and laws are discussed and agreed.

TASK 1: watch this 10 minute ILO video describing this history of this organisation and the labour standards and trade union rights that have been written into its conventions. As you watch this, please take some notes in answer to the following.

QUESTIONS 1: what are the ‘three keys’ of the ILO? Why did the ILO come into existence? What are the main achievements of the ILO’s Workers Group? What conventions did it publish in what years? What role did it play in important historical events of the 20th Century?

187 countries are members of the ILO – only Andorra, Bhutan, Liechtenstein, Micronesia, Monaco, Nauru and North Korea are not – and membership obliges each country to put into practice five fundamental rights for its people:

- a) freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining

- b) the elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labour

- c) the effective abolition of child labour

- d) the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation, an

- e) a safe and healthy working environment (see International Labour organisation).

The most important thing to understand about the ILO are its Conventions. These are agreements about labour rights and laws that are written by the ILO after discussions with people who represent governments, employers and workers. When a country ‘ratifies’ a convention, it agrees to update its national laws in line with that convention’s standards. But not all member countries have signed up to all of the ILO’s conventions, and not all of those countries that have signed up to them are implementing them through their legal systems.

TASK 2: The International Trade Union Confederation monitors the implementation of workers rights across the world. We would like you to check its latest Workers Rights report (click here) where each country is given a 1 (good) to 5 (bad) grade. Search the country table for three different countries: i) the one you live in, and ii) two others where items of clothing that you own were made. For each country, write down its 1-5 score, and click its name to see if there is any information that explains that score. If worker rights violations are mentioned – where the country scores are higher – take some notes on the details.

QUESTIONS: For countries where ‘workers rights violations’ are mentioned, what do these violations involve? Make a list. How does this make you feel about the items of clothing you have that were made in countries which violate labour rights? Write down your thoughts.

iii. Workers’ rights in the fashion industry

Next we take a look at some recent reports about workers’ rights in the fashion industry in different parts of the world. Because of the cut-throat competition between fashion’s brands, retailers and manufacturers, and the ways in which competitive pressures got worse during the COVID-19 pandemic, these rights have been severely damaged for many garment workers over the past few years.

TASK: We have read the summaries of the news articles below, and click the links on two that seem interesting to you. Read them carefully to answer the following questions.

QUESTIONS: What rights seem to have been denied the workers in the stories that you have read? In which countries were these rights under threat? Which fashion brands and retailers were mentioned? Who and/or what was said to be responsible for these rights being taken away? Who or what could pressure governments to give these rights back? Were these rights solidly in place before the pandemic?

- Poverty wages: “Lidl, Zara’s owner Inditex, H&M and Next have been accused of paying garment suppliers in Bangladesh during the pandemic less than the cost of production, leaving factories struggling to pay the country’s legal minimum wage” (Guardian, January 2023).

- Insecure employment: “Garment workers [in Pakistan] such as Abdul Basit, 35, claimed to have been charged by police with batons outside a factory which is reported to have fired more than 15,000 workers since the start of the coronavirus pandemic. … he hadn’t been paid since March. “We’re insecure workers and we can be fired at any time,” he said. Like many workers, Basit doesn’t have a direct contract with the factory, leaving him vulnerable” (Guardian, May 2020).

- Sexual assault & harassment: “After revelations of sexual violence in Lesotho garment factories, where jeans are made for brands such as Levi’s, workers fought for better conditions. But now Covid-19 has hit the fashion industry, those gains may be lost” (Guardian, August 2020).

- Union-busting: “Myan Mode, a garment factory on the outskirts of Yangon, Myanmar, produces men’s jackets, women’s blazers and coats for Western fashion companies like Mango and Zara. Since the start of the coronavirus pandemic, it has seen a decrease in orders from international retailers. That was why it let go almost half of its 1,274 workers in late March … Three fired sewing operators … said the factory was taking an opportunity to punish workers engaged in union activity [because] of the 571 who had been dismissed, 520 had belonged to the factory’s union” (New York Times, July 2021).

- Forced labour: “The Xinjiang region produces more than 20% of the world’s cotton and 84% of China’s, but according to a new report released on Tuesday by the Center for Global Policy there is significant evidence that it is “tainted” by human rights abuses, including suspected forced labour of Uighur and other Turkic Muslim minority people” (Guardian December 2020).

- Unsafe conditions: “Sewing machinists and others with jobs in garment factories have among the highest rate of coronavirus deaths among working women in the UK, according to an analysis by the Office for National Statistics. Twenty-one Covid-19 deaths among women aged between 20 and 64 in the “assemblers and routine operatives” category were registered between 9 March and 28 December 2020, giving the group a death rate of 39 per 100,000 women” (Guardian, February 2021).

NB these six themes come from a 2023 workers’ rights blog post on the Ethical Consumer website.

iv. Standing together for garment workers’ rights

In principle, garment workers are supposed to enjoy the rights that would give them dignified work, from conception to creation to catwalk, but these rights have to be fought for, both by people in each part of the supply chain (for example when garment workers or fashion models form labour unions), and by soliarities across different parts of the supply chain (for example, when consumers, businesses and labour unions hold each other accountable). In this section, we will look at both.

TASK 1: Watch this short ILO video in which garment factory workers and owners in Bangladesh talk about the importance of unions in their workplaces. This video was made in 2015, two years after the Rana Plaza factory complex collapse.

QUESTIONS: How were individual workers treated by management before they formed a union? Write down some examples. What does membership of a union allow workers to do together? Write down some examples. Why does the video say that union membership is good for the garment industry?

TASK 2: Watch this two video playlist in which the Clean Clothes Campaign explains the Bangladesh Accord – a legally binding agreement between brands, labour unions and factory owners which ensures that garment factories are safe places to work – and why brands need to list on their websites the names and addresses of the factories where their clothes are made.

QUESTIONS: How did the Rana Plaza collapse show that brands’ ‘robust standards’ about worker rights and safety were not enough? How have brands, labour unions, factory owners and governments worked together since to make garment factories in Bangladesh safer to work in? Who pays for the inspections? What happens to factories that are found to be unsafe? Where else are these ‘Enforceable Brand Agreements’ taking shape? Why is it important for brands to be transparent about the factories where their clothes are made? Who will find this information useful? How do these videos ask us to show solidarity with garment workers?

EXTRA STUDY: find out which brands have and have not signed the Bangladesh Accord here. What have your favourite brands done? Find out which brands have and have not made the Transparency Pledge here. What have your favourite brands done? And see how labour rights groups across Asia are holding brands legally accountable for human rights violations during the COVID pandemic here.

v. Reflection

At the end of module 3a, we asked you to think about how you might act in solidarity with garment workers who are similar to you in some ways, and different in others. In module 3b we have shown how NGOs channel these energies by asking us to help them put pressure on brands, retailers, factory owners and governments to give garment workers the rights that are enshrined in international law. Garment workers, as we have seen, also claim those rights for themselves.

We want to finish this module by thinking about what Manifesto point #1 means by ‘dignified work’. The International Labor Organisation works with the concept of ‘decent work’, which they define as:

“Productive work for women and men in conditions of freedom, equity, security and human dignity. Decent work involves opportunities for work that: is productive and delivers a fair income; provides security in the workplace and social protection for workers and their families; offers prospects for personal development and encourages social integration; gives people the freedom to express their concerns, to organize and to participate in decisions that affect their lives; and guarantees equal opportunities and equal treatment for all.

ilo.org

But the NGO CARE International argues that, for women in particular, ‘decent work’ is not enough. What makes ‘decent work’ dignified is if women have the power to access and control that work and what they are paid for it. What can prevent women from having this power often happens outside the workplace because, in addition to their paid work, many are likely to do unpaid work at home looking after children or elderly relatives. So dignified work can exist for women only if men and boys share this unpaid care work equitably. Dignified work is also connected to who spends the money that women earn when they bring it home. Women’s wages are often given to husbands, fathers or other male relatives to manage, and they are spent in ways that support others in the household (unlike men’s wages, CARE argues). Decent work can therefore be provided inside a workplace, but dignified work involves women being able to decide how and on what the wages they earn from this work are spent outside the workplace (for more, see CARE link). This is where workers rights, and human rights more generally, are connected.

QUESTIONS: Who can empower people working along each and every garment supply chain to enjoy the ‘dignified work’ that manifesto point #1 dreams of? We know that, as consumers, we have a part to play. But how can we contribute in other ways? It’s not just about the decisions we make about what clothes to buy. Who else has the power to create dignified work? And how can we/they work together?

You can express your answers in any way you like: writing, sketching, photoshopping, whatever works for you!